Guest Writer Cengiz K. Fırat (R) Ambassador

The Hejaz Railway stands as one of the most evocative infrastructure projects of the late Ottoman era: a narrow-gauge line that once stretched from Damascus toward the holy cities of Islam, designed to bind distant provinces to the empire’s heart, facilitate pilgrimage, and project state presence in the Arabian Peninsula. A century later, fragmented by war and neglect, the line is being eyed for revival. In recent years, Türkiye has become a critical partner in resurrecting portions of the corridor, raising the possibility of reconnecting old routes—and perhaps even tying them into broader trans-regional networks stretching toward Europe.

Founding Ambition and Early Function

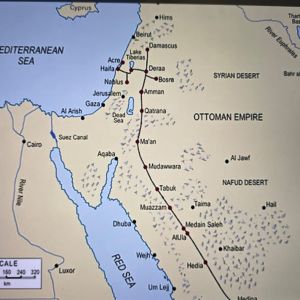

Ordered in March 1900 under Sultan Abdülhamid II, the Hejaz Railway was intended to link the Ottoman capital (ultimately via Istanbul → Damascus) with Islam’s holy cities in Arabia, namely Mecca and Medina. The plan envisioned a journey shorter and safer than the traditional camel caravans, and was pitched not only as a service to Muslim pilgrims but also as a tool of imperial cohesion and control. The Germans played a key role in the engineering and technical design, notably under the leadership of Heinrich August Meissner, who later became known as Meissner Pasha. The project drew financing from imperial coffers and donations (including zakat) from Muslims across the empire.

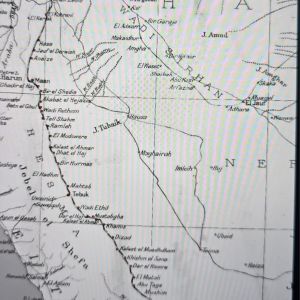

Between 1900 and 1908, the line was extended south from Damascus through modern Syria, Jordan, and into the Hejaz. The main line officially reached Medina in 1908, though the section all the way to Mecca was never completed. The railway covered approximately 1,300 km of challenging terrain, including desert expanses and mountainous stretches. Its branches also included one from Deraa toward Haifa on the Mediterranean.

For pilgrims, the railroad transformed what had been a perilous weeks-long journey into a matter of days, with more reliable water supply systems and station facilities en route. Trade likewise benefited: agricultural goods, manufactured wares, and vital supplies could move faster. Strategically, the Ottomans used it to dispatch troops, munitions, and administrative control to southern provinces more efficiently. The project was a potent symbol: modernization, religious legitimacy, and imperial reach combined in steel rails.

Yet even before World War I, the railway suffered attacks from local Bedouin groups resisting its intrusion into desert regions. When the Arab Revolt erupted in 1916, the line became a prime target: sections—especially between Ma‘an and Medina—were repeatedly sabotaged, disabling the railway’s usefulness. With the collapse of the Ottoman state after 1918 and the drawing of new national borders, the line fell into ruin. Several segments remained in partial use for local transport, but large stretches were abandoned.

Modern Revival: Türkiye, Syria, Jordan, and Beyond

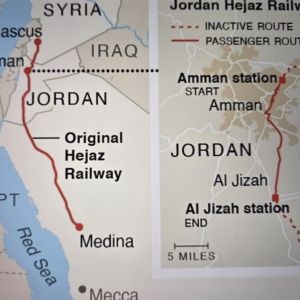

In 2025, Türkiye, Syria, and Jordan signed a preliminary agreement to revive the historic Hejaz Railway corridor. In a trilateral meeting in Amman, diplomats and transport ministers endorsed a draft Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for joint railroad, transportation, and infrastructure cooperation.

Türkiye’s Commitments and Strategic Role

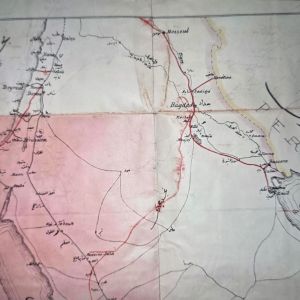

Türkiye has committed tangible support: one of the immediate responsibilities is to assist in restoring about 30 km of missing track superstructure in Syria’s Hejaz stretch. Turkish agencies are also working on corridor integration, particularly by examining ways to restore land freight and transit routes through Syria to Jordan—reopening overland commerce between Türkiye and Jordan after many years of suspension.

Beyond track restoration, Türkiye seeks to strengthen its Red Sea access via Jordan’s Aqaba port by integrating rail and road corridors. The idea is that trade from Türkiye could move south through Syria and Jordan to Aqaba and onward via maritime routes. The Ankara government is drafting technical and logistical plans, coordinating working groups with Syrian and Jordanian partners.

Route Scope: From Damascus southward, or Istanbul all the way?

The current restoration focus centers on the Damascus → Medina segment (including Jordanian stretches). That is the “low-hanging fruit” in terms of terrain complexity and legal jurisdiction. The portion north of Damascus—toward Syria’s northern rail network and ultimately Türkiye —is more complex due to war-damage, gauge alignment, political control, and costs. Still, Turkish officials have spoken publicly about ambitions to tie into trans-European routes, effectively making the revived Hejaz a leg in a corridor linking Europe to the Red Sea and beyond.

Some press reports suggest that the complete Istanbul → Mecca vision is being floated in strategic roadmaps. But in practice, the MoU and technical plans as of 2025 do not commit to rebuilding every section immediately. The northern interconnections, especially inside war-torn Syria, remain uncertain.

If fully realized, the route could tie Europe (via Türkiye) to the Arabian Peninsula, forming a contiguous land-sea trade and pilgrimage corridor. But that remains aspirational pending political consensus, engineering feasibility, funding, and cross-border coordination.

Purpose: Heritage, Tourism, or Core Infrastructure?

The revival project wears two hats: heritage and functional infrastructure. On one hand, the Hejaz Railway carries potent religious and historical symbolism. Restoring it appeals to regional pride, pilgrimage nostalgia, and heritage tourism—a draw for those wishing to traverse the old Ottoman pilgrimage route by rail.

On the other hand, the agreements and early steps make clear that governments see tangible economic benefit: freight, transit, corridor connectivity, port integration (especially via Aqaba), and revitalized cross-border commerce. Gulf state financing (e.g. UAE interest) suggests this is not merely sentimental. The restored rail could serve as a regional multimodal corridor.

Challenges & Strategic Risks

• War damage and infrastructure decay: Syria’s conflict has inflicted severe disruption. Bridging, tunnels, station structures, trackbeds—many segments require full reconstruction rather than repair.

• Technical compatibility: Gauge, signaling, rolling stock, electrification or diesel standards, and border procedures must align.

• Political coordination: Border controls, transit rights, security, customs regimes and national sovereignty concerns complicate cooperation.

• Financing & timelines: Ambitions must be matched with resources. Building or restoring long stretches will take years, and not all segments will be immediately viable.

• Saudi participation: To reach Mecca, Saudi Arabia’s consent and partnership will be essential—both politically and logistically.

Potential Impact & Regional Significance

If successful, the revived Hejaz Railway could symbolize renewed regional integration, blending culture and commerce. Türkiye would gain a southern transit route to the Red Sea; Jordan and Syria would benefit from revived trade and infrastructure investment; pilgrims and tourists would gain a dramatic, historically resonant corridor. More broadly, it could function as a model for reconstructing fractured transport networks in a region segmented by conflict and shifting borders.